Canada’s Top Ten Paramedic Dispatch Calls in Canada (and what to do in the first 5 minutes)

Entertainment-only disclaimer

This is for entertainment and general education. It is not medical direction, not a protocol substitute, and not a replacement for clinical judgment. If you attempt to cardiovert a rhythm using a countdown voice and “positive energy,” please document it under “spiritual interventions.” If your partner says, “Hold my coffee,” treat that as a red flag.

Where the “Top Ten” comes from

Canada does not publish one national, standardized list of dispatch “patient problem” categories. What we do have are transparent local reports. Hamilton Paramedic Service publishes a “Top 10 Patient Problems by Dispatch Category” table in its 2024 annual report: Fall (14%), Dyspnea (13%), Ischemic chest pain (9%), Unknown problem (7%), Unconscious (7%), Abdominal/pelvic/perineal/rectal pain (6%), Unwell (3%), Motor vehicle collision (3%), Behaviour/psychiatric (3%), and Diabetic emergency (3%). A similar profile appears in the Middlesex-London Paramedic Service 2020 Performance Report, which lists dyspnea, falls, weakness/dizziness/unwell, ischemic chest pain, abdominal pain, mental health, MVC, and unconscious among top dispatch problems.

How to use this guide

Dispatch gives you a label; your assessment builds the working problem. For each call type below you’ll read the red flags to hunt for, the questions that change decisions, and a “first five minutes” plan framed for EMR, PCP, and ACP scopes. Scope differs by province and employer, so keep all actions inside local protocols and medical direction. The goal is faster stabilization, cleaner classification, and earlier commitment to destination and notifications.

Why dispatch categories matter for training

These ten call types make a solid training backbone: common, high-risk, and perfect for five-minute drills that test assessment, decisions, and teamwork consistently.

10) Diabetic emergency

Diabetic emergencies can be wonderfully reversible or deceptively complex. Funny example: the patient says, “I took my insulin,” then adds, “I forgot to eat,” and their fridge contains only condiments and ambition. Hypoglycemia can look like intoxication; hyperglycemia can look like “just sick.” Treat the brain first.

Red flags include altered LOC, seizure, inability to protect airway, profound diaphoresis, rapid breathing, dehydration, and infection as a trigger.

Key questions: diabetes type, insulin or oral meds, last meal, dosing errors, recent illness, vomiting, typical glucose range, and whether a CGM reading matches reality.

First five minutes: EMR checks glucose if available, gives oral glucose when safe, protects the airway, and reassesses quickly for response. PCP gives dextrose or glucagon per protocol, monitors ECG, and looks for triggers. ACP prepares for airway protection when mentation is poor, manages severe metabolic derangement per protocol, and treats dehydration or shock physiology while choosing the right destination. Do not declare victory after the number improves; the cause still needs management.

For teaching: after treating hypoglycemia, ask “why” immediately. Missed meals, medication errors, infection, and alcohol use are common triggers and determine whether the patient is safe to remain or needs transport. For hyperglycemia, watch for dehydration and mental status changes and treat the patient, not the device reading. A CGM is helpful, but it’s not a replacement for assessment.

9) Behaviour / psychiatric

Behavioural calls are where communication is a clinical skill, not a soft skill. Funny example: a bystander yells “calm down,” which has the same effectiveness as yelling “stop bleeding” at a laceration. Your goals are safety, de-escalation, and medical screening, because physiology can masquerade as “behaviour.”

Red flags are self-harm intent or plan, violence risk, severe agitation with hyperthermia, ingestion or overdose, hypoxia, hypoglycemia, head injury, and unsafe environment.

Key questions: intent, plan, means, substances, medical complaints, psychiatric history, and supports. Ask directly and calmly about suicide and self-harm.

First five minutes: EMR focuses on safety, distance and exits, de-escalation, and requesting police when required by local policy. PCP adds medical screening (vitals, glucose, oxygenation) and tox considerations per protocol. ACP uses protocol-driven chemical restraint only when necessary and pairs it with continuous monitoring and a search for medical causes. The best restraint is often a good plan, enough resources, and a calm team that doesn’t rush the patient into a corner.

For teaching: behavioural calls are medical calls until proven otherwise. Do vitals and glucose early, and assume substances are involved until the story proves they aren’t. Keep your language consistent and non-confrontational; it lowers temperature fast. Funny-but-true: the loudest person on scene is rarely the most helpful historian. Choose one calm speaker and limit the audience.

8) Motor vehicle collision (MVC)

MVC calls are loud, chaotic, and full of conflicting witness statements. Physics, however, is consistent. Funny example: the driver says “I’m totally fine,” while wearing a seatbelt sign like a sash and asking you to “just check me quickly.” The not-funny part is that internal injuries are quiet until they are not.

Red flags include high-energy mechanism, intrusion, ejection, rollover, death in same vehicle, long extrication, anticoagulant use, chest or abdominal pain, and evolving pallor and anxiety.

Key questions: speed, restraints, airbags, point of impact, number of patients, extrication time, loss of consciousness, and current symptoms.

First five minutes: EMR prioritizes scene safety, triage, hemorrhage control, and spinal motion restriction only when indicated. PCP adds monitoring, IV access, pain control per protocol, and destination aligned to trauma criteria. ACP supports extrication with advanced analgesia or sedation within direction, prepares for airway compromise, and escalates traumatic shock management early when signs appear. Reassess after the adrenaline drops; that is when injuries start telling the truth.

For teaching: MVC calls reward two habits—mechanism matters, and reassessment matters more. Take one minute to understand the crash before you get pulled into emotions and opinions. Look for seatbelt signs, chest pain, abdominal tenderness, and subtle shock. If you’re doing extrication, plan airway and analgesia early; pain and fear make patients fight you, even when you’re helping.

7) Unwell / weakness-dizziness

“Unwell” is dispatch shorthand for “could be anything.” It’s also the call that rewards a disciplined set of vitals more than heroic improvisation. Funny example: the patient says, “I’m just tired,” while the spouse says, “They walked into a wall.” Believe the spouse; they are the unofficial quality-assurance officer of the household.

Red flags include fever with tachycardia, hypotension, hypoxia, new confusion, focal neuro deficits, inability to ambulate, chest pain, and signs of bleeding.

Key questions: baseline function, timeline of decline, infection symptoms, medication changes, hydration, blood loss, near-syncope, and hidden chest discomfort or shortness of breath.

First five minutes: EMR gets full vitals, glucose if available, and reassesses early because trends are clues. PCP adds ECG, IV, stroke and sepsis screening, and treats what you find rather than what dispatch called it. ACP prepares for escalation—airway support and fluid or pressor pathways per protocol—because “unwell” is sometimes the quiet name for shock. If you feel bored on an “unwell” call, double-check the vitals; boredom is not a clinical indicator.

For teaching: “unwell” becomes manageable when you translate it into pathways. Is this infection and possible sepsis, neuro and possible stroke, cardiac and possible dysrhythmia, or metabolic and possible hypoglycemia? A quick screen for each prevents tunnel vision. Fun example: “I’m dizzy” can mean “the room spins,” “I’m going to faint,” or “I’m nauseated,” so make them describe it without the word “dizzy.” The answer changes everything.

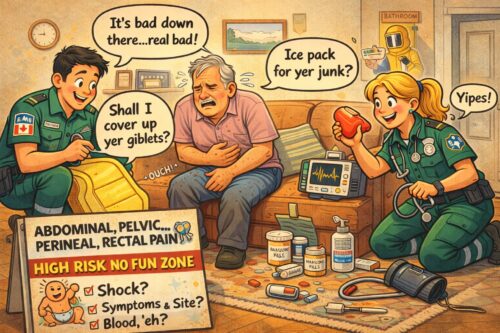

6) Abdominal / pelvic / perineal / rectal pain

Abdominal pain is the complaint that refuses to be specific. Funny example: the patient points to their entire torso and says, “It hurts here,” as if anatomy is optional. The risk is that abdominal pain ranges from uncomfortable to catastrophic, and the catastrophic ones are sometimes polite.

Red flags include shock, rigid abdomen, GI bleed, syncope, pregnancy or postpartum status, sudden severe pain, pain out of proportion, and back pain with abdominal symptoms suggesting vascular catastrophe.

Key questions: onset, location and migration, vomiting or blood, melena, last bowel movement, urinary symptoms, pregnancy status, anticoagulants, and what has relieved nothing.

First five minutes: EMR treats shock early, keeps the patient warm, and avoids delays when instability is present. PCP establishes IV access, gives antiemetic and analgesia per protocol, and reassesses vitals for trend because abdominal disasters declare themselves over minutes. ACP provides advanced analgesia carefully, anticipates hypotension after analgesia in volume-depleted patients, and prepares for rapid deterioration with airway and resuscitation plans. When abdominal pain is paired with instability, treat it as time-critical until proven otherwise.

For teaching: abdominal pain rewards calm urgency. Don’t let the patient’s normal conversation trick you into slow pacing. Check perfusion, look for shock, and reassess frequently. If the patient is pregnant or possibly pregnant, treat the situation as higher risk until proven otherwise. And if the pain is “sudden and worst-ever,” treat the words as a symptom, not drama.

5) Unconscious / altered level of consciousness

Unconscious calls are dramatic, but the first move is often simple: open the airway and ventilate. Funny example: a bystander says “not breathing,” while the patient snores like a chainsaw; obstructed breathing is still breathing badly. Another classic: the patient becomes fully awake the moment police arrive. Document objectively, keep the scene safe, and treat what is real.

Red flags are airway compromise, respiratory depression, seizure activity, hypoxia, hypotension, and evidence of toxins or trauma.

Key questions (to witnesses): last seen normal, witnessed collapse, seizure history, diabetes, medications, substances, recent illness, and any naloxone or glucose already given.

First five minutes: EMR prioritizes airway positioning, suction, BVM as needed, AED readiness, and rapid packaging. PCP adds glucose testing and reversal agents per protocol, ECG monitoring, and seizure precautions. ACP brings advanced airway options, ETCO2 monitoring, seizure management pathways, and peri-arrest readiness. Do not delay ventilation while searching for the perfect diagnosis; physiology does not wait for your differential to feel complete.

For teaching: if the patient is altered, you own the airway. Positioning and ventilation are treatments, not “waiting steps.” Use your partner: one manages airway and monitoring, the other gathers witness history and checks for clues such as meds, tox, and trauma. The funny rule is, “If you can hear snoring, you have an airway problem.” The serious rule is, “If you can’t hear anything, you may have a worse airway problem.”

4) Unknown problem

Unknown problem is dispatch’s polite way of saying, “We don’t know; you figure it out.” It often starts with “not acting right,” which can mean delirium, hypoxia, infection, stroke, intoxication, hypoglycemia, medication error, or trauma nobody witnessed. Funny example: the family says the patient is “confused,” then adds, “He normally argues about the thermostat for fun,” and yes, that baseline matters.

Red flags are any abnormal vitals, new confusion, unequal pupils, focal deficits, respiratory depression, fever with hypotension, or signs of injury.

Key questions: last known well, what changed today, falls, new meds, substances, pain, fever, and chronic conditions that decompensate. If there is a caregiver, ask what is different today in plain language and then let them talk.

First five minutes: EMR anchors on safety, ABCs, full vitals, glucose if available, and frequent reassessment. PCP adds ECG, IV, focused neuro and respiratory exam, and treats the reversible killers found early (hypoxia, hypoglycemia, opioid toxicity, shock) per protocol. ACP expands to advanced airway and hemodynamic support when indicated, while resisting “CSI paramedicine” that delays fundamentals. If the story is messy, let physiology lead and let the narrative catch up.

For teaching: build a structured “unknown” routine so you don’t drift. Vitals, glucose, pupils, focused neuro screen, lung sounds, skin, temperature, and a fast med or substance check will catch most time-critical problems. If you find nothing, that is still information; document what you ruled out. Humour reminder: “unknown” is not permission to improvise wildly, it’s permission to be methodical.

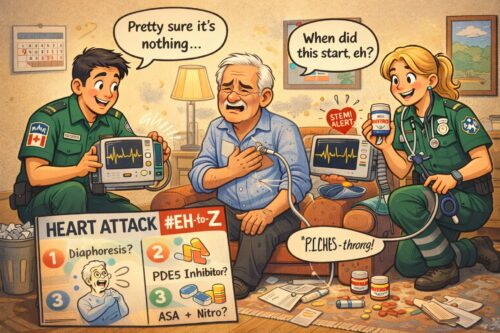

3) Ischemic chest pain (suspected ACS)

Chest pain calls begin with optimism and should end with disciplined caution. The patient often says “it’s indigestion,” because nobody wants to believe their heart is misbehaving. Funny example: the patient’s plan was to “sleep it off,” which is a great plan for mild reflux and a terrible plan for myocardium. If the patient waited days, skip the scolding and move faster.

Red flags include persistent pressure-like pain, diaphoresis, pallor, syncope, hypotension, new heart failure signs, dysrhythmias, and atypical presentations in older adults, women, and patients with diabetes.

Key questions: OPQRST plus exertional triggers, associated shortness of breath, nausea, prior cardiac history, anticoagulants or antiplatelets, and PDE5 inhibitor use if nitrates are relevant.

First five minutes: EMR reduces exertion, monitors closely, uses oxygen only if indicated, ASA given by mouth and chewed and requests ALS early. PCP gets a 12-lead quickly, follows local antiplatelet and vasodilator pathways, manages pain per protocol, and commits to destination with early notification where required. ACP manages instability (cardioversion or pacing per protocol), provides advanced analgesia with hemodynamic awareness, and activates STEMI pathways early when criteria are met, because your ETA is part of the treatment.

For teaching: your first 12-lead is a time stamp, not a trophy. Repeat ECGs when the story evolves, because ischemia can be dynamic. In the field, “normal ECG” is not a discharge plan; it is one data point. And remember the Canadian phenomenon of patients who apologize for calling while actively infarcting—reassure them, keep them still, and make the system move faster than the clot.

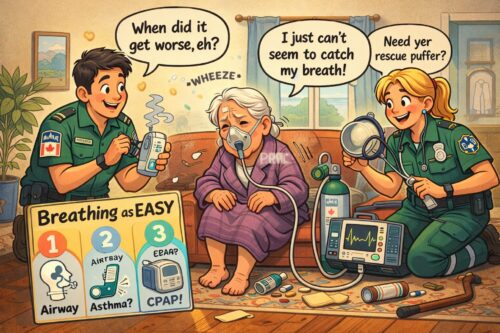

2) Dyspnea (shortness of breath)

Chest pain calls begin with optimism and should end with disciplined caution. The patient often says “it’s indigestion,” because nobody wants to believe their heart is misbehaving. Funny example: the patient’s plan was to “sleep it off,” which is a great plan for mild reflux and a terrible plan for myocardium. If the patient waited days, skip the scolding and move faster.

Red flags include persistent pressure-like pain, diaphoresis, pallor, syncope, hypotension, new heart failure signs, dysrhythmias, and atypical presentations in older adults, women, and patients with diabetes.

Key questions: OPQRST plus exertional triggers, associated shortness of breath, nausea, prior cardiac history, anticoagulants or antiplatelets, and PDE5 inhibitor use if nitrates are relevant.

First five minutes: EMR reduces exertion, monitors closely, uses oxygen only if indicated, and requests ALS early. PCP gets a 12-lead quickly, follows local antiplatelet and vasodilator pathways, manages pain per protocol, and commits to destination with early notification where required. ACP manages instability (cardioversion or pacing per protocol), provides advanced analgesia with hemodynamic awareness, and activates STEMI pathways early when criteria are met, because your ETA is part of the treatment.

For teaching: your first 12-lead is a time stamp, not a trophy. Repeat ECGs when the story evolves, because ischemia can be dynamic. In the field, “normal ECG” is not a discharge plan; it is one data point. And remember the Canadian phenomenon of patients who apologize for calling while actively infarcting—reassure them, keep them still, and make the system move faster than the clot.

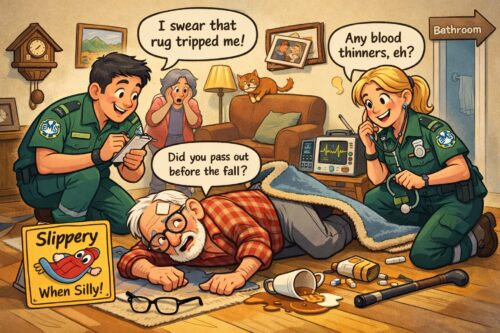

1) Falls

Falls are number one because gravity is undefeated and “I was just going to the bathroom” is Canada’s most common mechanism of injury. The scene can look calm: tidy home, polite patient, apologetic family. Then you notice the anticoagulants, the head strike, or the subtle facial droop no one mentioned because “it’s probably just from sleeping funny.” Funny example: the patient blames the rug; the rug sits there like it has never done anything wrong in its life.

Red flags are head injury on anticoagulants, neck pain with mechanism, prolonged down time, hypotension, confusion, new neuro deficits, and hip pain with shortening or external rotation. Also treat any “fall” with a vague pre-fall story as possible syncope until proven otherwise.

Key questions: What happened before the fall? Any loss of consciousness? Any chest pain, palpitations, shortness of breath, or sudden weakness? Any blood thinners? Any head strike? What is baseline mobility and mentation?

First five minutes: EMR focuses on safety, ABCs, bleeding control, spinal motion restriction only when indicated, full vitals, glucose if available, and a quick decision about whether this is trauma, medical, or both. PCP adds syncope screening, 12-lead when appropriate, IV and analgesia per protocol, and frequent reassessment for evolving shock or neuro change. ACP expects complex pain control, potential airway support if mentation declines, and rhythm management if the fall was really a cardiac event wearing a trauma coat.

For teaching: treat “fall” as a trigger to look for the hidden medical cause. A quick routine helps: scan for blood thinners, check glucose early, do a neuro screen, and ask one witness to tell the story from the beginning without interruptions. Funny but true: if three people tell you three versions, the vitals are the only honest narrator. If the patient fell and now can’t get up, don’t let the scene turn into a furniture-moving contest; stabilize, package, and move.